Community-Led Conservation of Freshwater and Fisheries in Latin America

Meet the communities that are stewarding global freshwater ecosystems for nature and people.

Latin America is famously home to the Amazon River — a freshwater system unlike any other. The river is home to about 15% of the world’s fish species and more aquatic megafauna than any other place on Earth, and it discharges more fresh water than any other river on the planet.

It also supports more than 45 million people living in its basin, including nearly 2.2 million Indigenous People and 400 different ethnic groups.

Local residents and Indigenous Peoples play an important role in stewarding these lands and waters, and their leadership is key to the Amazon’s future sustainability.

In fact, Indigenous territories and protected areas already cover roughly 50% of the Amazon River Basin.

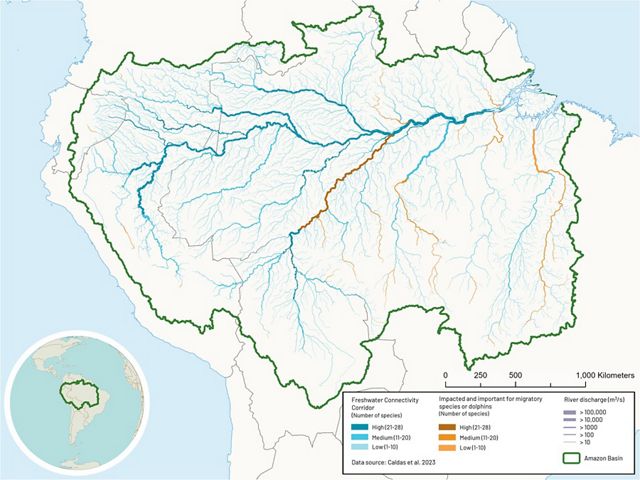

This map shows the location of freshwater fisheries projects in South America, including the Caquetá River Basin, the Napo River Basin, the Marañón and Ucayali River Basins, and the Tapajós and Lower Amazon River Basin.

The Amazon River Basin’s freshwater biodiversity is sustained by an extensive network of healthy free-flowing rivers that are connected to floodplains and wetlands. Maintaining freshwater connectivity is key to the long-term sustainability of biodiversity and people that depend upon it.

But the Amazon River is facing enormous pressure as nearby land development, hydropower dams, invasive species, pollution and other threats continue to degrade its waters and surrounding landscapes.

To conserve the entire Amazon River Basin, and all who depend on it, we must address these different and connected challenges — and fast.

That’s why we’re working directly with local communities in key watersheds throughout the Amazon River Basin — in both the Amazonian headwaters in the Andean mountains (Peru, Colombia and Ecuador) and the lower Amazon (Brazil) — to co-create tools and resources that bolster human well-being and freshwater biodiversity.

Listen to sounds of the Amazon River Basin as you scroll.

-

The Amazon River — connecting life throughout the basin

The below map shows river reaches in the Amazon Basin (basin boundary in green) that are identified as freshwater connectivity corridors (blue gradient) and rivers that are impacted but still host migratory species, turtles, or dolphin species (orange gradient). Color gradients reflect species richness. Adapted from Caldas et al. 2023.

This map shows river reaches in the Amazon Basin that are identified as freshwater connectivity corridors and rivers that are impacted but still host migratory species, turtles, or dolphin species.

The upper and lower reaches of the Amazon River are connected by the water and migratory species that travel between them.

The Dorado catfish, an iconic species found in the Amazon River, is an important symbol of that connectivity. It has the longest known freshwater migration in the world, swimming from its spawning grounds in the Andean mountains to its nursery habitat in the Amazon estuary, and then back to the Andes to spawn.

Watch An Epic Journey

The Great Migration of the Dorado Catfish, Connecting Life Throughout the Amazon

Ecuador

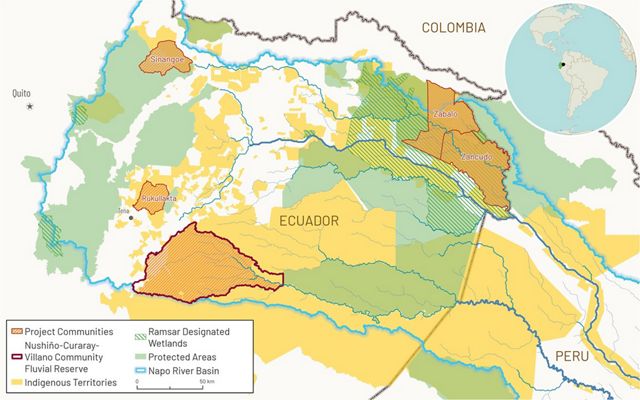

This map shows projects, communities, and protected areas in Ecuador, coded by color.

A closer look: Ecuador

-

Napo River Basin, Andean Amazon, Ecuador

-

2011

-

- The Amazonian Dorado catfish

- Paiche (Arapaima)

- Giant river otters

- Black caiman

- Giant river turtle (“Charapa”)

- Freshwater rays

- Pink and gray dolphins

-

- Deforestation and land-use change for agriculture and ranching

- Unsustainable fishing and hunting

- Mining and oil production

- Hydropower and dams

- Water pollution

- Gender inequities

-

- Governance and capacity-building of local governments and communities

- Community regulations and strategies for freshwater resources conservation

- Community fluvial (free-flowing river) reserves

- Community-led monitoring system using traditional knowledge

- Culturally-aligned livelihood strategies

- Gender and equity initiatives

-

- Indigenous Peoples Organizations (Zábalo, Zancudo Cocha, Rukullakta, Sinangoe, Kichwa Indigenous Nation of Pastaza (PAKKIRU), and Waorani Indigenous nation (NAWE)

- National Organization of Indigenous Communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE)

- Ministry of the Environment, Water and Ecological Transition

- Research Centers and Universities: National Institute of Biodiversity (INABIO) and National Research Institute on Fisheries (IPIAP)

- Local governments of Napo, Pastaza and Sucumbíos

River Guardians: Protecting the Napo Watershed

Spanning 6 million hectares, the Napo watershed in Ecuador covers 25 different ecosystems. As its name implies, the watershed is home to the Napo River, which begins high in the cloud forests of the Ecuadorian Andes and eventually meets the Amazon River in Peru. Nearly 70% of the Napo Basin is under the stewardship of Indigenous Peoples. These communities are considered the guardians of the rivers and are active stewards of their natural resources.

The Challenge

Much of the Napo watershed is still intact due to the active management practices of local Indigenous communities. Encroaching development, however, is putting pressure on the region, threatening freshwater ecosystems and biodiversity. Currently, Indigenous rights to mitigate these threats are limited. The Constitution of Ecuador recognizes Indigenous communities’ right to form autonomous governments; however, the rights to water and underground resources (i.e., oil and minerals) remain in government control. With partners, our initiative supports Indigenous communities to strengthen their full territorial and resource management, respecting their rights.

The Opportunity

In the Napo watershed, TNC partners with Indigenous nations to strengthen local governance and co-create conservation strategies to protect their freshwater ecosystems. We work with the A´I Cofan, Kichwa and Waorani Indigenous nations to take the following conservation actions:

- In the Sinangoe community, part of the A´I Cofan Indigenous nation, we support patrols by community guards looking for threats to the rivers, such as illegal mining.

- In the Rukullakta community, we promote a community-led monitoring system for water quality and freshwater biodiversity.

- In the Gomateon and Sinangoe communities, we identify the presence of mercury and evaluate the level of threat from mercury contamination.

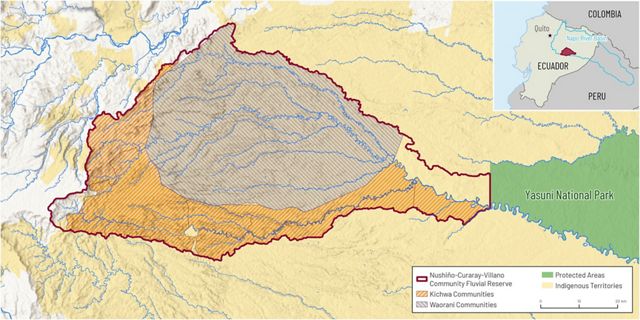

- In the Curaray watershed, we worked with nearly 80 Indigenous Waorani and Kichwa communities to create the Nushiño-Curaray-Villano Fluvial Reserve that will protect about 1,900 kilometers of river and 26,000 hectares of wetlands in an area rich in biodiversity (read on for more details).

A River Reserve for the Napo Watershed

In 2023, the Waorani and Kichwa Indigenous nations declared the free-flowing rivers of the Nushiño-Curaray-Villano area as a Fluvial Reserve (see below map). The community-led protection of a free-flowing river in the Amazon is the first of its kind and will maintain a freshwater connectivity corridor.

This area is particularly important for freshwater biodiversity, with around 200 fish species that are key for subsistence fisheries of 4,300 Indigenous Peoples and local communities living on this territory.

TNC works with leaders such as Norma Nenquimo, directive of the Waorani Indigenous Nation of Ecuador, to support the fluvial reserve.

The Local Community in Action

Alexandra Narváez, a member of the A´I Cofán nation, won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2022, alongside Cofán community member Alex Lucitante, for leading an effort to defend her ancestral territory and sacred rivers from threats such as mining.

Alexandra is part of the Sinangoe’s community guard that patrols their territory for illegal activities. TNC supports the community guard by providing equipment and technical assistance.

Looking Forward

At TNC, our 2030 goals guide our efforts and unite programs across the organization. In Ecuador’s Napo Basin, by 2030, we will conserve more than 400,000 hectares of lakes and wetlands and 13,000 kilometers of river systems. We will work with 23 communities to implement conservation activities aimed at improving the condition of freshwater ecosystems within their territories.

Most of these communities will also pursue sustainable economic development activities (e.g., sustainable fishing plans, aquaculture, non-timber forest production) to contribute to food security and sovereignty and reduce pressure on freshwater ecosystems.

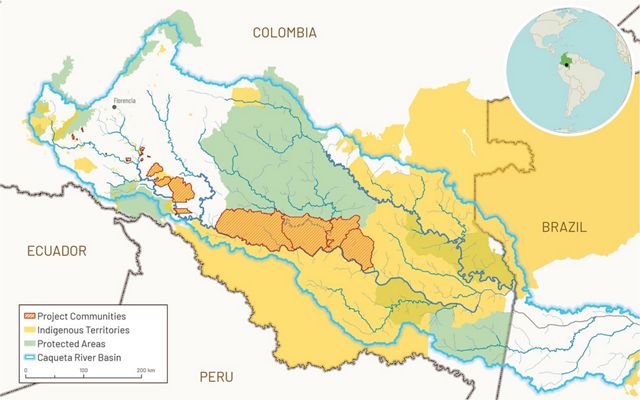

Colombia

This map displays freshwater fisheries projects in Colombia, including current ones as of 2023 and future projects. It also shows protected areas, Indigenous territories, and the area of the Caqueta River Basin.

A closer look: Colombia

-

Caquetá River Basin, Andean Amazon, Colombia

-

2011

-

- Catfish (Dorado catfish, banjo catfish, gilded catfish, talking catfish)

- Giant river turtle (“Charapa”)

- Giant river otter

- River dolphins

-

- Unsustainable fishing and hunting

- Mercury contamination from deforestation and mining

- Large-scale cattle ranching

- Water pollution

- Gender inequities

- Territorial conflicts (Intercultural agreements)

-

- Community-led monitoring (Community Science)

- Culturally-aligned livelihood strategies

- Culturally-aligned conservation/restoration strategies

- Gender equity initiatives

- Inter-community freshwater conservation agreements

- Elevating community voices in territorial territorial management plans

-

- Local and Indigenous Communities and Organizations

- Local governments Solano Municipality and Caquetá Government

- Organización Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía Colombiana (OPIAC) or National Organization for Amazon Indigenous Communities

- Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Cientificas (SINCHI)

- Ministry of the Environment

- Fundación Proterra

-

- 2024 TNC article: Monitoring networks that seek to conserve biodiversity in Caquetá

- 2024 TNC article: Women Guardians of the Territory and Ancestral Amazonian Memory

- 2020 TNC article: Ancestral Memory: Key to Saving the Amazon

- TNC article: Colombia

- 2020 TNC article: Keepers of the Amazon

Water People: Stewards of the Caquetá River Basin

The Caquetá River Basin spans more than 250,000 square kilometers across both Colombia and Brazil. More than 65% of the Basin’s land, including freshwater ecosystems, are managed by local communities and Indigenous Peoples. Four primary traditional cultural groups (Mambe-ambil-rape, Yage, Yurupari and Jaibanas) include more than 40 Indigenous tribes residing here. Some of these communities refer to themselves as “water people” — a signifier of their close relationship with the river.

The Challenge

While much of the Caquetá is either protected by national parks or under the management of Indigenous people, it still faces significant threats. Large sweeps of alluvial plain have been drained, deforested, and converted to fields, leading to the degradation of freshwater ecosystems. Unsustainable fishing and gold mining also threaten freshwater biodiversity and the well-being of those in Caquetá. Impacts from gold mining include water pollution from the use of mercury. Mercury bioaccumulates in the food chain and causes neurological problems for children and pregnant women who eat fish.

Looking Forward

At TNC, our 2030 goals guide our efforts and unite programs across the organization. In Colombia’s Caquetá Basin, by 2030, we will conserve more than 110,000 hectares of lakes and wetlands and 2,000 kilometers of river systems. We will work with 35 Indigenous people and local communities to implement conservation activities aimed at improving the condition of freshwater ecosystems within their territories. These communities will also implement sustainable economic development activities (e.g., sustainable fishing plans, aquaculture and non-timber forest production) to contribute to food security and sovereignty and reduce pressure on freshwater ecosystems.

Brazil

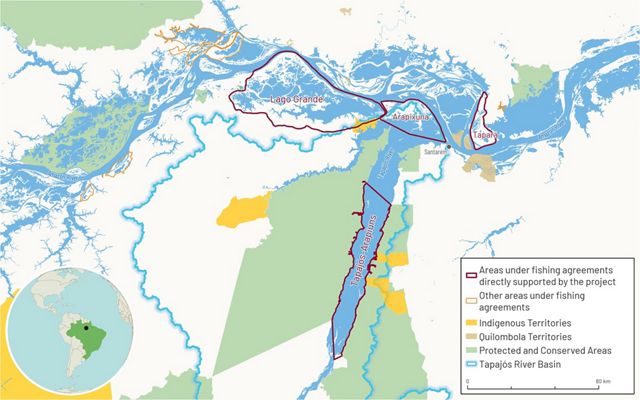

This map highlights the freshwater fisheries project area in Brazil, along with project communities, areas under fishing agreements directly supported by the project, other areas under fishing agreements, Indigenous territories, protected and conserved areas, and the location of the Tapajós River Basin.

A closer look: Brazil

-

Tapajós River Basin, Amazon region in the state of Pará

-

2006

-

- Amazon river dolphin (known locally as boto, a vulnerable species)

- Arapaima gigas (known locally as pirarucu, Amazonian giant air-breathing fish)

- Tracaja (turtle species)

-

- Mercury contamination of fish from artisanal mining

- Decreased water quality due to cyanobacteria blooms

- Loss of key fish breeding habitats

- Lack of recognized rights over aquatic resources

- Lack of training to meaningfully participate in resource management decision-making

-

- Fisheries monitoring and mapping of fisheries territories

- Community education

- Sustainable fishing practices

- Income alternatives

- Increasing local communities and women’s decision-making power

-

- Associação Movimento dos Pescadores do Baixo Amazonas (MOPEBAM)

- Society for Research and Protection of the Environment (Sapopema)

- Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará (UFOPA)

- TURIARTE (women-led tourism and handicraft cooperative)

- Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA)

- Federação das Organizações Quilombolas de Santarém (FOQS)

- Associação Amélias da Amazônia

-

- TNC Podcast: Tapajós Waters

- TNC Article 2023: New fisheries agreement

- TNC article: The Tapajós River

- TNC Article: Leading role of indigenous peoples

- 2021 TNC Article: Partnerships to Strengthen Science in the Amazon

- 2020 Cool Green Science Blog: Putting Communities at the Center of Freshwater

Helping Communities Exercise Their Rights Over Freshwater Resources

The Tapajós River — one of the largest tributaries of the Amazon — is a waterway of sizable impact. The river, and its main tributaries, stretch roughly 1,770 kilometers. The entire river basin is home to 1.6 million people from approximately 14 ethnicities and 32 Indigenous groups, including the riversides (subsistence and artisanal fishers).

The Challenge

While 40% of the Tapajós River Basin is protected by a combination of protected areas and Indigenous lands, unsustainable development and high poverty levels pose a significant risk to the region’s freshwater biodiversity, and local communities that rely on these ecosystems.

Across the basin, cattle ranching, agriculture, infrastructure development, and mining have contributed to impacts on rover water quality and connectivity.

Research indicates that conservation and development projects that engage local communities are more likely to achieve sustainable and successful results for both people and nature. However, the planning and monitoring of the social and ecological impacts related to these infrastructure projects and conservation strategies at the local level have largely been neglected. It is essential that these processes also consider the traditional knowledge of the communities involved. Incorporating this knowledge can lead to more effective and culturally sensitive outcomes.

The Opportunity

When local communities secure their rights to land tenure, access to natural resources, and cultural preservation while also participating in decision-making processes, both freshwater biodiversity and local livelihoods trive. In the Tapajós region and other areas of the Lower Amazon, TNC collaborates with riverside communities and Indigenous Peoples to empower them in enhancing sustainable fisheries management and encouraging their meaningful involvement in monitoring aquatic biodiversity.

In the Tapajós, TNC and local partners address sustainable fishing practices. Two fishing agreements (Lago Grande and Arapixuna) designed to improve the health of fisheries and benefit more than 70 local communities have been submitted for approval by the state government.

Additionally, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará (Western Pará Federal University), a TNC partner, conducted research on mercury contamination of fish and people throughout the Tapajós Basin. Preliminary results indicate that mercury concentrations are much higher than safe limits. TNC is working with local communities including the Parauá, Suruacá, Aldeia Solimões, Apacê and Cassuepá to amplify their voices among state and federal government decision-makers so that issues like these are brought to light.

We are working to enhance the visibility of women’s roles in fishing. Over 600 women have been reached through training activities focused on rights and gender inclusion.

Local Community in Action

In 2022, with the support of TNC and partners, Sr. Edinaldo, a fisherman and a riverside leader, met with members of the state government representatives to discuss the challenges facing the fishing sector in the Tapajós region. This meeting marked the first time that the fishermen’s movement of Tapajós had a voice in discussion with decision-makers regarding public policy solutions.

Did you know?

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining operations comprise almost 38% of the total global mercury (Hg) emissions and are a threat to food and water quality in the Amazon and elsewhere. Mercury contamination is damaging to both freshwater fish ecology and the people who rely on fish for food and livelihoods.

Looking Forward

By 2025, together with partners, we will increase territorial and aquatic resources rights of 100 communities in the Lower and Middle Tapajós and Lower Amazon Rivers and adopt sustainable fishing practices that protect and conserve freshwater biodiversity across 1,700 kilometers of large rivers and more than 400 hectares of wetlands.

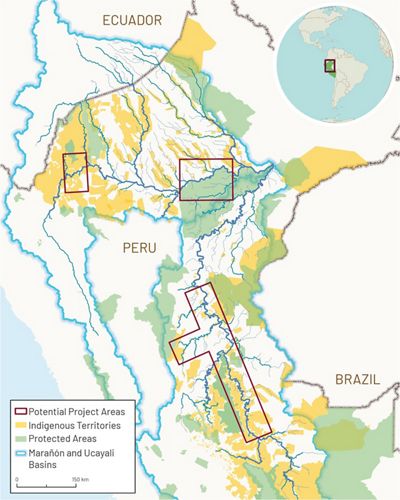

Peru

This map of Peru highlights potential freshwater fisheries project areas, as well as Indigenous territories, protected areas, and the location of the Marañón and Ucayali Basins.

A closer look: Peru

-

Marañón and Ucayali basins

-

1990

-

- Pirarucu (Arapaima gigas), or paiche, is the second largest freshwater fish in the world.

- Carachama (Pseudorinelepis genibarbis) is a type of armored catfish native to the freshwater rivers and streams of the Amazon basin in South America.

- Boquichico (Prochilodus nigricans), Palometa (Mylossoma albiscopum), Sabalo (Brycon amazonicus) and Llambina (Potamorhina altamazonica) are the main species caught in Peruvian Amazon fisheries.

-

- Loss of fluvial connectivity

- Formal and illegal mining

- Pollution from oil spills

- Potential overfishing

- Ornamental fish trafficking

-

- Support co-management fishery governance with local communities and fishers’ associations

- Strengthen knowledge of fisheries to inform decisions through Indigenous knowledge and western science

- Enhance transboundary collaboration to address cross-border challenges and build synergies at different levels

- Promote fishing agreements to conserve rivers

- Grow technical capacity for fisheries management and promote fishing agreements for effective conservation

- Elevate Indigenous voices through Life Plans (Planes de Vida) that holistically integrate Indigenous territorial management and conservation goals with communities’ social, economic, and cultural well-being

-

- Instituto del Mar del Perú (IMARPE)

- Instituto del Bien Común (IBC)

- Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS)

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

- Gobernanza Sur

- Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest

- Organización Nacional Nade Mujeres Indígenas Andinas y Amazónicas del Perú (ONAMIAP)

-

- TNC article: Ríos de Vida Perú

- TNC Webpage: The Nature Conservancy in Peru

- TNC article: Working with Indigenous Peoples to Protect the Peruvian Amazon

Free-flowing Rivers for Fish and Fishing Communities

TNC’s freshwater fisheries work is just beginning in Peru, focusing on the community engagement in the Ucayali and Marañón basins — areas rich in biodiversity and vital to Indigenous communities. We’re partnering with the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP, the representative organization for the Indigenous Peoples of the Peruvian Amazon) to identify communities closely tied to freshwater and fisheries. These basins still have free-flowing rivers that are essential for the health of the Amazon, serving as migration corridors for fish, turtles, and river dolphins.

Early Successes

Working with our partners, we’ve laid the groundwork to help freshwater fisheries and local communities thrive by taking these key steps:

- We supported the development of 14 Life Plans in the low Marañon Basin. Indigenous Life Plans and territorial planning promote better fishery management by combining conservation goals with the social, economic, and cultural priorities of Indigenous communities.

- We supported the passage of 3 freshwater conservation agreements to help protect biodiversity while supporting local livelihoods and food security. These agreements empower communities to care for nature and benefit from it sustainably.

- We evaluated four fishing organizations in the Ucayali Basin using a practical tool (Organizational Maturity Index) that assesses the management capacity of artisanal fishing organizations. This helps identify what they’re doing well and where they can improve in strengthening both sustainable fishing and local communities.

- We assessed the state of fisheries in Peru’s Amazon Basin to better understand fishing activity, including stock status, threats, and opportunities to engage partners. This will inform conservation projects that bolster both freshwater ecosystems and human well-being. For example, we found that 60 commercial catfish fishers, 5 Indigenous Peoples, and over 100 communities rely on 420 kilometers of river.

- We are supporting the implementation of a fishing monitoring program in the Ucayali region in collaboration with the Peruvian Marine Institute (IMARPE). Our next step will be to involve the community in monitoring their own freshwater resources to better management planning.